What exactly is an endling? Just ask Allison Kleine Hegan ’05. “An endling is an individual that is the last of its species or subspecies; when the endling dies, the species becomes extinct,” she explained. In November, Allison’s book “No More Endlings: Saving Species One Story at a Time” was published by Motivational Press. The book features short articles by conservationists, professors and researchers, along with a fact sheet on each endling profiled. Former FSHA biology teacher Nancy Power is one of the authors.

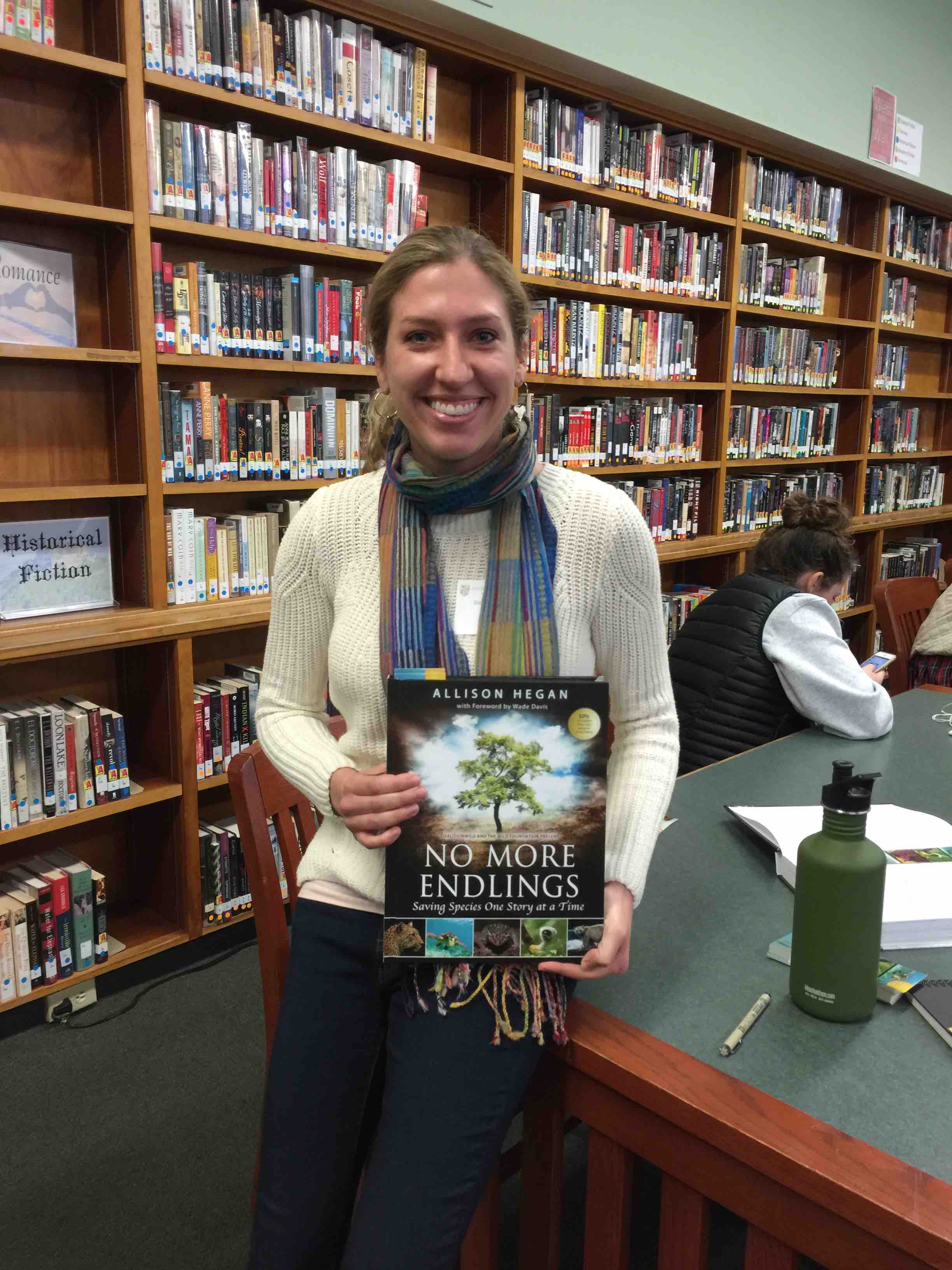

Allison stopped by FSHA in the winter for a book discussion. Students, faculty and staff crowded into the library to hear about her career path and what she learned while compiling the book. “I do believe we are at a turning point in our world, either on the cusp of great environmental catastrophe or great opportunity to make our world better. My hope is we make the right decision, and with the help of the contributors in this book and the many others out there who are also fighting for our environment, we can still imagine a future with no more endlings.”

Science Department Chair Leslie Miller is using “No More Endlings” in her AP Environmental Science class this upcoming year. “It is great for teaching our students about conservation, strategies to protect species, and ecology and environmental career paths,” said Leslie.

To find out more about the book editing process, we asked Allison about her experience.

What made you decide to edit No More Endlings?

When I first started working on No More Endlings, I felt a strong need to do something to help protect the environment and wildlife. It was 2010, and at the time, I was living at my parents’ house, like so many recent college grads, and had desperately been searching for full-time work in my field. I had majored in geography and environmental studies at the University of Wisconsin, but I ended up applying to whatever was available and would have gladly accepted anything that came my way. After settling for dog-walking and temp work, I was really discouraged by the fact that I couldn’t be doing something to support my passion. Then, after posting to a group on LinkedIn, I received a suggestion from a member to work on a book.

Initially, I didn’t really have any idea what I was doing or how I was going to get people to contribute, but I knew the message was worth fighting for. I took it one day at a time and tried to learn as much as I could from friends in the publishing world and bloggers on the internet. There was certainly some hesitation at the start, and I questioned whether I really had anything to offer the book with no directly-related field experience of my own. Fortunately, I realized early on that I shouldn’t get bogged down in what I couldn’t do and should focus on what I could. I knew I could act as a kind of glue, bringing very different stories together from those working in the field to protect endangered species.

How did you pick your contributors?

Initially, I didn’t have any particular contributors in mind, just species. I made a list of those I wanted represented in the book and made a conscious effort to include a variety—mammals, plants, insects, fish, birds, and reptiles—and represent every continent. The only exception is Antarctica—although I did get a response back from an Antarctic research station when I reached out to them. Then I researched conservationists, activists, professors, photo and film journalists, and National Geographic explorers from around the globe who had worked closely with one of those species. Part of the reason the book is so large is because, surprisingly, most people said yes, and I didn’t want to turn anyone down who wanted to participate. Also, some of the people who came on board for one species requested to contribute an additional chapter on a different species with which they had also worked. No More Endlings shows just how broad conservation efforts can be and how necessary it is to have people coming from all angles to be successful in protecting a species.

What has been the response to the book?

The response has been very positive. No More Endlings is not on the New York Times’ bestseller list, nor has it reached millions of readers, but I never expected sales to be astronomical with a book of this nature. Those who have purchased No More Endlings have expressed that they find the book very inspirational and are amazed to see how an individual can intervene on a species’ behalf and make a substantial difference.

Often, people have expressed surprise by some of the species I chose to include in No More Endlings. For example, the hornet robberfly, which favors dung beetles for dinner, isn’t exactly glamorous. But it is the stories of the underdog species like the hornet robberfly which some readers have found to be the most enjoyable.

Originally, I intended the book to be a coffee table book for the general public, but the combination of stories, scientific sections, and photographs translate well in a classroom setting. I’ve had some success getting the book into the science curriculum in a few Southern California schools and hope to expand on this. A contributor from the book, who lives in Botswana, expressed an interest in bringing No More Endlings to local schools there as well.

Another contributor has proposed a possible partnership with National Geographic to make the book into a series, but it is too early to know if this will come to fruition.

What do you hope readers take away when they read No More Endlings?

Ultimately, my aim is for No More Endlings to help people make the connection between all species, their importance within each of their ecosystems, and their importance within our own lives. Animals and plants provide beauty in our world, food and medicine, pique our curiosity, inspire creativity and innovation, and enrich our lives in countless ways. The species on this earth are astounding in their diversity, and if they perish, they are likely never to exist again. I hope by highlighting just a fraction of them in this book readers will be encouraged to action.

For some species, the rate at which we are trying to save them may not be enough, and some have already gone extinct in our lifetime, and many more will likely follow suit. But to look at this or any environmental setback as hopeless, implies we should give up, and there is no point to even try to salvage the wreckage and protect what remains. Instead, we must maintain hope, perseverance, innovation, and pragmatic solutions to push the conservation movement forward.

Conservationists must be eternal optimists. However, I do believe we are at a turning point in our world, either on the cusp of great environmental catastrophe or great opportunity to make our world better. My hope is we make the right decision, and with the help of the contributors in this book and the many others out there who are also fighting for our environment, we can still imagine a future with no more endlings.

No More Endlings is available on Amazon. 50% of royalties go to conservation.

Please go to allisonhegan.com to learn more.