When I was in high school (back in the olden days), if I wanted to carry on a covert conversation in class, I had to undertake the dangerous work of writing and passing a note. For my students, such furtive exchanges happen via iPhone and are as often pictures or videos as they are texts. Where I would have written a paragraph (in cursive handwriting) about how boring my English class was, they send a SnapChat video of the boredom in process.

Of course my students — and Flintridge Sacred Heart students in general — are so enraptured by their studies that they would never do any such thing, but my point is more that our world is increasingly visual and that as responsible educators we have to reckon with this truth in our teaching: The world changes and so our classrooms and our practices as teachers must change.

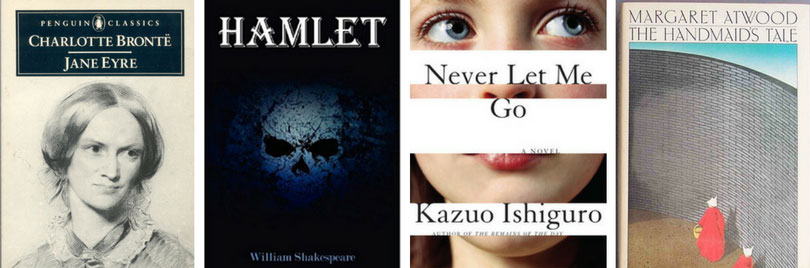

I am a teacher of English and literacy is still the heart of what I do: I teach reading and writing, and the cornerstones of my English IV course are canonical great books such as “Jane Eyre” and “Hamlet” and more contemporary classics such as Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale,” Kazuo Ishiguro’s “Never Let Me Go,” and Zora Neale Hurston’s “Their Eyes Were Watching God;” my students still learn grammar and vocabulary and strategies of argument.

Rethinking Literacy: Written vs. Visual

But my definition of literacy has grown more expansive in recent years in response to the fact that human communication is becoming less verbal and more visual: We tweet or text rather than blogging or emailing— and more likely we post photos to Facebook or Instagram. Whereas the average city dweller 30 years ago was exposed to 2,000 advertising images a day, she’s now exposed to 5,000. And while the communication or journalism major of the days of yore might have aspired to being a cub reporter, she’s more likely now to have her sights set on a social media coordinator gig.

When my students are alienated by the many pages of sumptuous descriptive detail in “Jane Eyre” and suggest it might be a less soporific novel if this descriptive excess were excised, I ask them why they think Charlotte Brontë “wasted” so much time describing faces and dresses and dining rooms. And if they’re stumped by this, I ask them how many images they imagine Charlotte Brontë saw in the course of an average day in Haworth Parsonage. Not many, they know— hundreds, thousands less than they do. Inevitably, they figure out that this is part of the gulf between their world and Brontë’s and the source of their difficulty with her. Description was once a pleasure to be savored, the means of drawing pictures in the mind when the world contained few. My students’ world is image-saturated and their minds no longer build images from written description with the ease and pleasure of nineteenth-century readers, or even so easily as we who grew up without smartphones and streaming video do. I began to feel recently that I needed to find a way to alleviate this growing alienation, to get them to savor such descriptions, to attend to the particular details of a given scene.

Instagram as classic close reading assignment

Some part of my answer is a now two-year-old assignment: It was Instagramming “Jane Eyre” last year. This year, it’s Instagramming Ishiguro and Atwood. In some ways it’s a classic close reading assignment, but it requires students to produce an image rather than an essay and their work is graded on how accurately and eloquently they bring to life the passage of the novel they’ve chosen. They pick a particular scene or image from the text that they translate into an image— a photograph to be shared on our class Instagram. Their first task is collecting quotations from the scene: details of setting and mood, descriptions of the postures, props, and expressions of the characters in the scene. This task forces them to read with a rigor and depth of attention they may never have exerted before. It’s an exercise in slow, deep reading.

Then, we do a tutorial on the basic rules of visual composition: leading lines, strong triangles, the rule of thirds, figure to ground, framing, viewpoint and perspective, cropping, use of light and shadow, texture, color, black and white. We talk about casting and makeup and costumes and props, and making do when you don’t have, say, a nineteenth-century bonnet. We “read” film stills from a variety of “Jane Eyre” films. My students don’t know how much they know about how images work, but they’re quickly fluent with the new vocabulary. And then they go to work.

From the creation of visual images come deeper insights

What they produce, as you’ll see in this post, is remarkable. And I have found that their understanding of a scene achieves a subtlety and sophistication that many of them wouldn’t be able to access through a conventional close reading essay precisely because they’re more visually than verbally literate. Allowing them to “write” in visual language, a language they’re more fluent in and discerning about provides a scaffolding for deeper insights. Intertwining visual and verbal literacy— the reading of literary texts and the reading and producing of images— seems to benefit both skill sets. The short talks they give about their artistic process and the significance of their chosen scenes are often some of the best work they do all year.

A post shared by Emily Wilkinson’s English IV (@fsha.english) on

There are certainly those who see ours as a culture in decline and see this increase in visual culture and decrease in verbal culture as signs of the apocalypse. I can’t feel that when I’m in the midst of grading these assignments. I see human literacy adapting rather than atrophying, and I feel deeply grateful to be a part of Flintridge Sacred Heart’s community of innovative educators who push me toward fresh teaching approaches.

More images from Ms. Wilkinson’s classes

To see all the images, please check out @fsha.english on Instagram

A post shared by Emily Wilkinson’s English IV (@fsha.english) on

A post shared by Emily Wilkinson’s English IV (@fsha.english) on

A post shared by Emily Wilkinson’s English IV (@fsha.english) on