As our students are just beginning to explore research topics for the Junior and Senior Resesarch Projects, Natalie Hodis ’17 reflects on her SRP experience last year.

Teenagers, as Lawrence Kohlberg described in his book “Stages of Moral Development,” are just beginning to step away from what we are told as fact by society and learning to find our own truths. I guess then my Senior Research Project is the perfect reflection of that internal transition that all of my classmates and I are going through. I began the SRP process with the question, “how do these two viewpoints coalesce in government?” We all have our own truths that are protected by our individual rights. However, they have to balance out with what is right for the community as a whole. I can’t go around murdering people even if I believe that it is just because it would harm those around me. That point where an individual’s rights and society’s rights intersect is difficult to define. It is obscured even more when you consider that whoever (or whatever party) decides where that point is also has their own self interest to calculate. I saw that this huge question was not one that I could answer as a high school senior since humankind still hadn’t determined the precise coordinates.

So I decided to narrow my focus to a specific time and place where a discussion of these rights was taking place and research that. During the Cold War, the debate between Russian socialism and American democracy was in full swing. While pure communism’s focus is solely on the well-being of the society, Americans argued that when the government defined what this well-being should be, then an individual’s rights were being undermined. The Soviet Union’s counter argument was that the same was happening in America but to the detriment to the society at a whole. While we championed democracy, they claimed that only those with money had a true say in our capitalist government and that the working class were left to the mercy of the laws they passed. In the midst of the developing tension between the two nations, literature flourished from this ideological conflict in both countries. One particular genre was especially adept at building upon this present and creating a future from it: dystopian fiction. Characterized by futuristic settings gone awry, the genre was able to navigate and deconstruct the present by predicting alternate worlds based off of it.

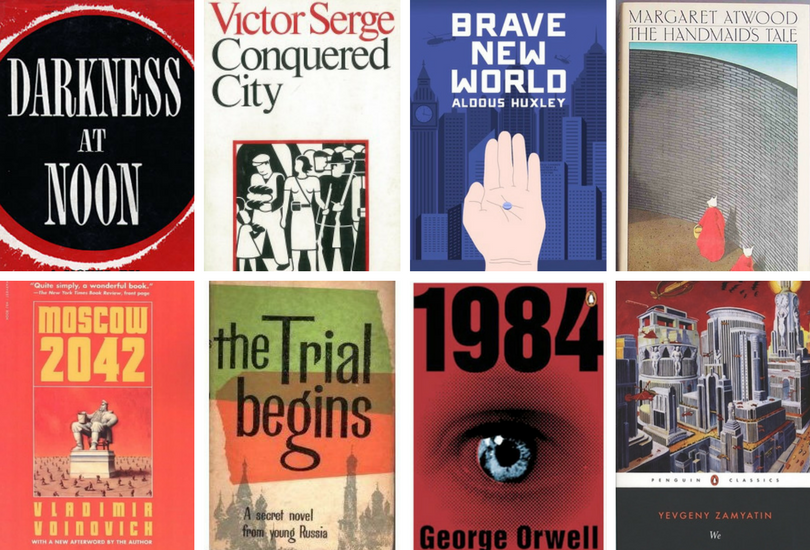

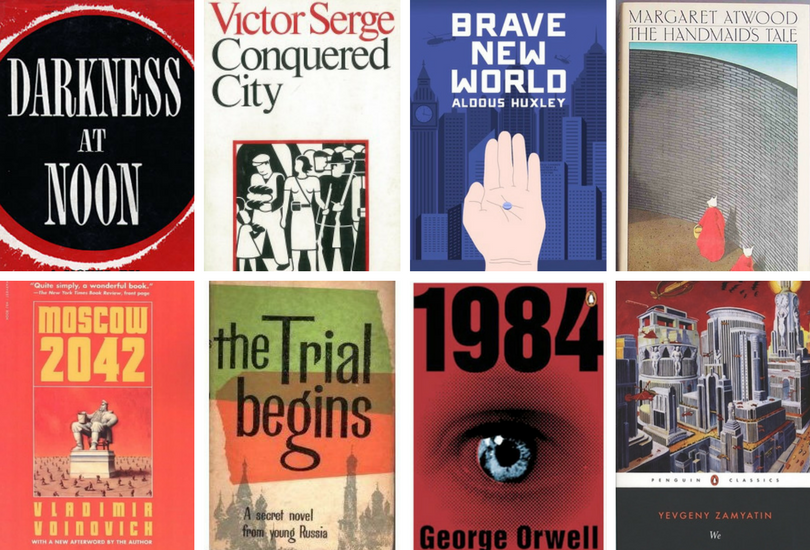

I picked eight novels of this genre and time period to study, including “The Handmaid’s Tale,” “1984,” “Brave New World,” “We,” “Moscow 2042,” “The Trial Begins,” “Conquered City,” and “Darkness at Noon.” With half written from a western perspective and the other from an eastern one, I hoped to create a complete picture of the Cold War. After reading, highlighting and studying, I came to see that these same issues of individual versus societal rights described thirty years ago are still relevant today. We are still haven’t found where the two paths intersect or even how to determine where it could be. History is cyclical in this way as the same issues come up again and again but in a younger generation that has forgotten the lessons of the past. I wanted now to find out if I could make others see this too. For if we are to start learning more from our past, we may get closer to our ideal future of balance between the individual and its society.

With all eight novels left in public places with markers, highlighted passages and a description of my project, I left it up to others to make the same connections that I did. Each location (Vroman’s Bookstore, Flintridge Bookstore and Coffeeshop, and the FSHA library) had two books, one from a western perspective and one from an eastern perspective, for people to write, draw and collect their thoughts in. After two weeks, I collected the books and reviewed the pages. From the responses of strangers I was able to deem my hypothesis correct. My research paper worked more like an experiment, where I took data and was able to measure the validity of my hypothesis not from my own thoughts but from the truth of others. By opening my project to all who wanted to participate, I democratized the research experience. My project became less an assertion of my own ideas and instead a platform to voice the thoughts of many.

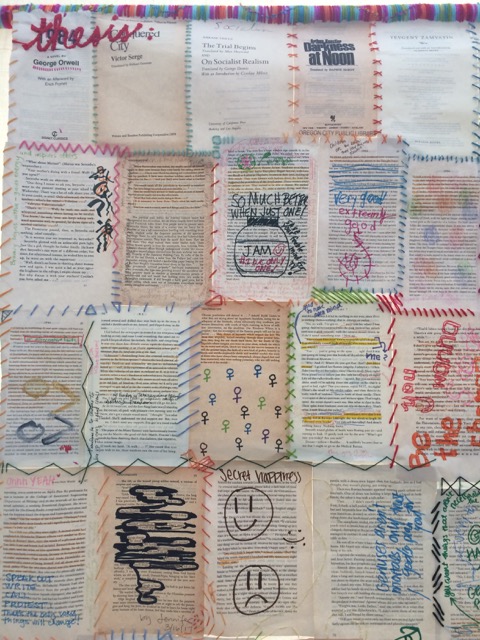

To present my data, I selected pages from each book that were especially interesting and sewed them together to create a tapestry of sorts. With the title pages of each followed by the pages in decreasing page number, all the eight books have been sewn together to create a new novel. This new book is for our generation because from the letters printed on thirty years ago to the drawn thoughts of today stained into the pages it is connected to our present. The pages are still changing and will continue to change, because every time I present my research project I have markers next to it for others to add their thoughts.