Selecting a research topic is probably the most critical and the most frustrating part of the entire process, as discussed in my prior post about the emotional spectrum of the information search process. It is fraught with uncertainty, which is the enemy of the grade-conscious high school student. According to Project Information Literacy, 37% of college freshmen surveyed said that “delineating assignment parameters and defining and selecting a topic” was the most difficult research task they faced during their first year of college. One reason for this is that high school projects are generally structured around a specific topic defined by the teacher. Research economic factors that led to the Civil War, find out what contributed to the ultimate success of the Woman’s Suffrage movement, discuss climate change reversal success stories, and so on. These are all valuable research opportunities, and important topics, but they are also predetermined by the instructors and therefore serve only as examples of research topics. Learning by example is not as effective as learning by doing.

Here at Flintridge Sacred Heart Academy, we’ve taken steps to include new opportunities for student-driven topic selection in our research program. Starting in the second half of sophomore year the girls craft original research questions (in English II) that stem from classroom conversation, readings, and a central theme provided by the teacher. (Presenting students with a theme is preferable to presenting them with a topic, since it defines the purpose of the project without limiting or prescribing specific topics.) This first serious research question is really difficult for the students, and they work to draft, revise and gradually find a final question over a number of weeks. It is a critical writing assignment more than anything really, as wordsmithing is a major part of getting to the heart of an idea.

The Read Around

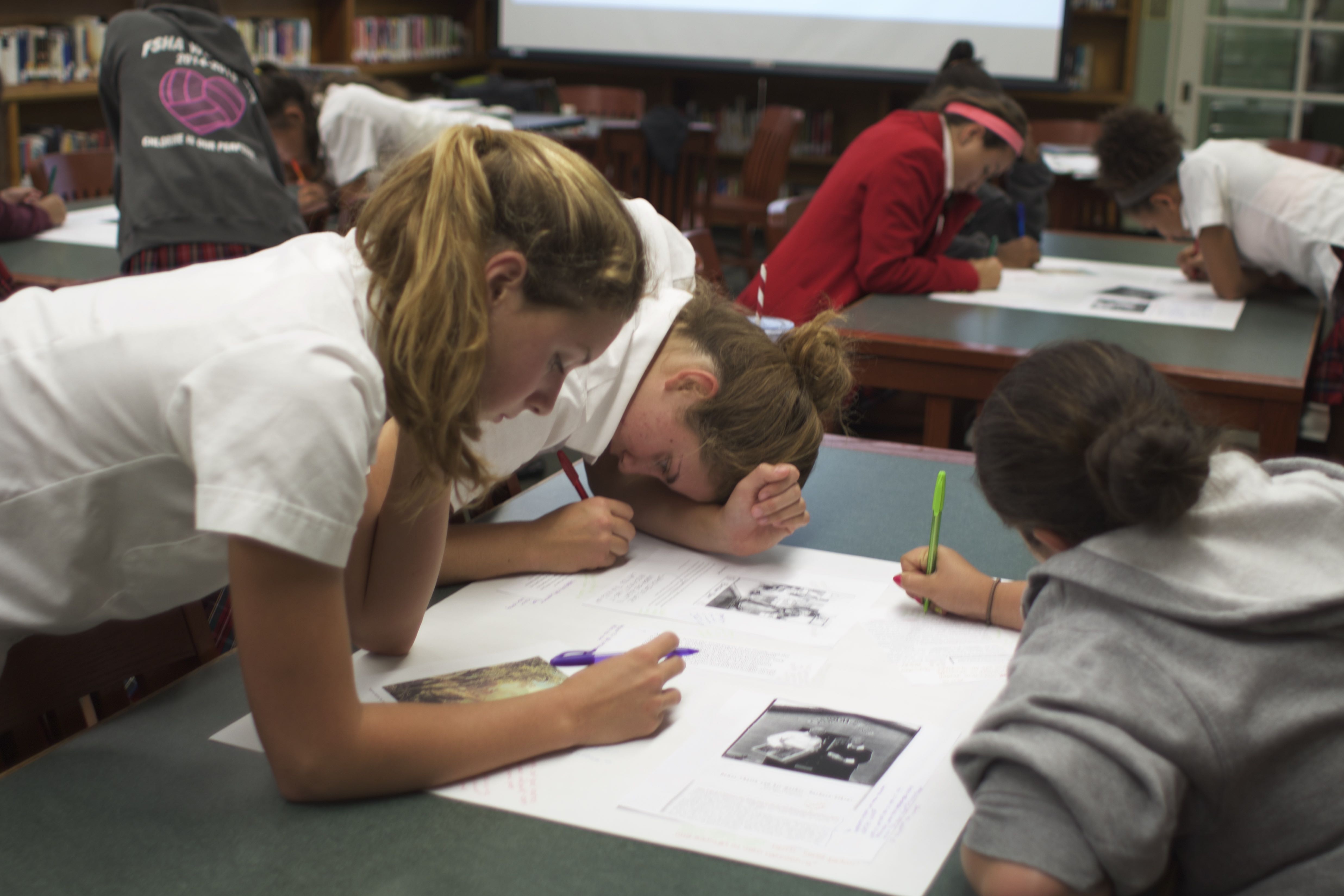

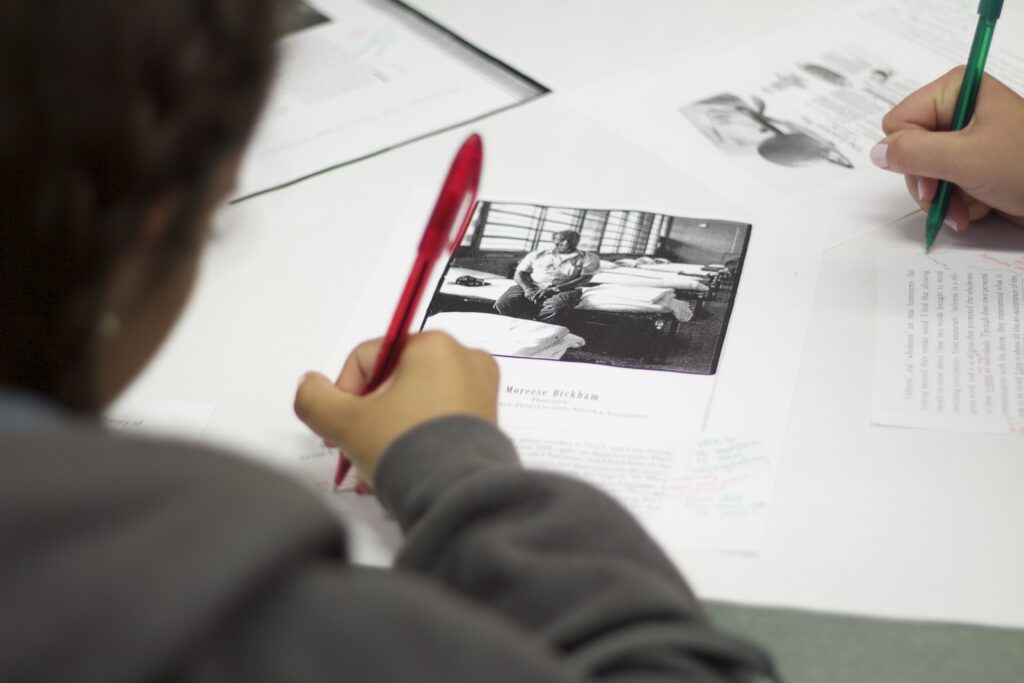

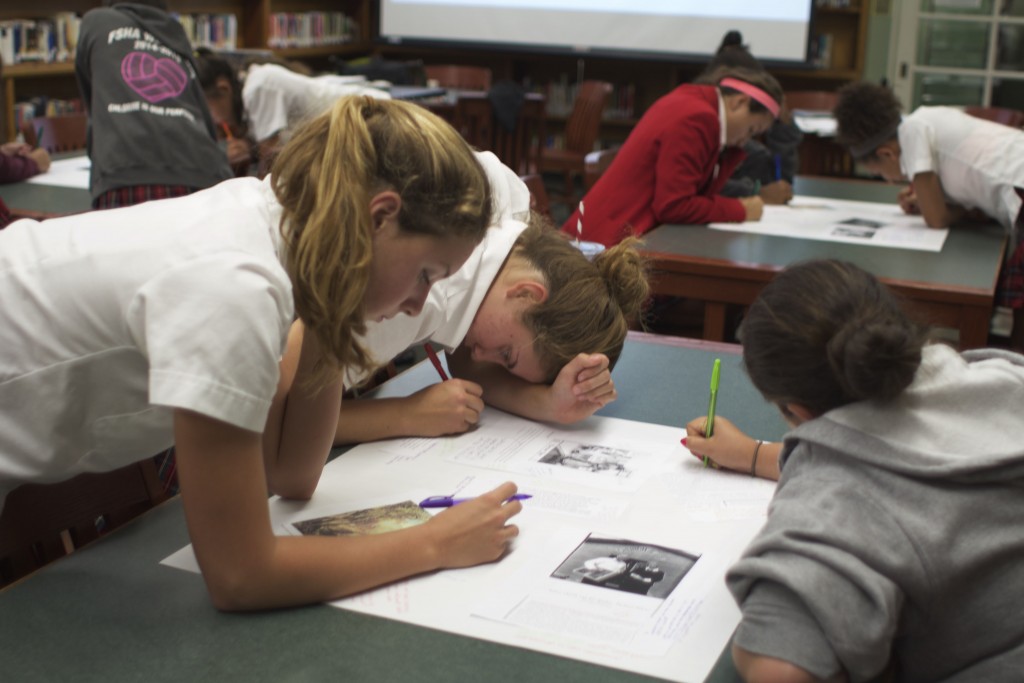

At the junior and senior levels this year we used an activity we called a read around to help students generate topic ideas about project themes (american studies for juniors, social/environmental justice for seniors). I first participated in a read around at a Research Relevance Colloquium at The Castilleja School in Palo Alto. Inspired by a session run by Sarah Kelley-Mudie, Upper School Librarian at Hawken School in Ohio, I developed a version of the activity she called a write around, renaming it in order to focus students on the close reading of texts (many visual) in order to generate ideas.

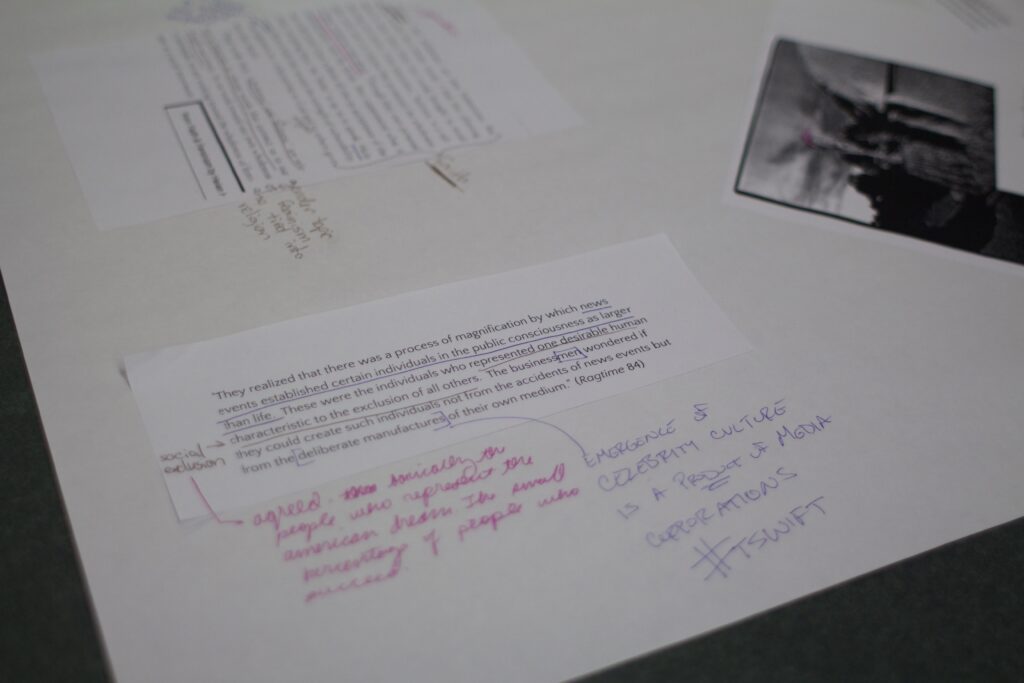

Long story short (and now credit has been given, so I can just blather on), we gathered dozens of artifacts related to the project themes and created posters that included around six items each. Items included photographs, social media campaigns, infographics, charts, paintings, poems, and excerpts from literary and informational texts. The students spent time quietly examining each piece (don’t worry, I’m almost done describing the lesson), recording their thoughts, and eventually using their ideas to brainstorm as a group and then again individually. The result was what we called a ‘brain dump:’ raw material that students would spend a few weeks refining in order to develop a topic proposal.

This is where things get instructionally dicey. How do you help a student go from point a to point b? Maybe a more accurate question is, how do you help a student go from point –a to point b? In a lot of cases, students can a) identify a personal interest based on something they’ve read/viewed, and b) relate that interest loosely to the project theme, but rarely can they c) frame the idea in a way that is viable in terms of conducting research. Let me help you out with a very realistic example.

Frances is a junior. She needs to come up with an American Studies topic, meaning a topic that examines what is essentially American about America. She loves following celebrities’ Instagram feeds, so she starts reading about her favorite celebrities in an effort to come up with a topic. For a week she reads articles on websites like the Huffington Post, Slate, the Guardian, Entertainment Weekly, and so on. She theorizes that celebrities are actually exploited by our media, observing that we must be a shallow culture overly influenced by materialism and fame. She turns in this research questions to her teacher:

Why are Americans so shallow and materialistic, and how has that evolved over time?

She receives a low score on her topic proposal and question, but does not understand why. Isn’t she trying to discover something about American culture, after all?

- First, Frances is making assumptions right off the bat, which is deadly for research. She’s already decided that Americans are shallow and materialistic, rather than asking if they are shallow and materialistic.

- Not to mention the fact that she is grossly overgeneralizing/oversimplifying (what does Americans mean here? young? white? not white? brunette? flat-footed?).

- Finally, she’s asking herself to accomplish too much (evolved over time is a life’s work, not an 8-10 high school paper).

- Oh, and also, she didn’t read beyond news blurbs, which were probably about the daily lives of celebrities and not about celebrity culture as a thing.

Does this make her idea bad? Absolutely not. Does it mean she has to start over? No way. Then, How? How does she proceed?

Honestly, that’s a much longer answer than I can give here. It involves the massaging of this topic until it is reshaped into something more like: What does celebrity culture in the 21st century indicate about American materialism, and how have consumer habits shifted/changed with the advent of celebrity-focused social media outlets? Ok, that’s not perfect. I just made it up. But here’s what it does (and doesn’t) do. It doesn’t assume. It doesn’t overgeneralize. It focuses on a time period. It focuses on a single behavior. It leaves the question wide open to an answer that will be revealed by research.

Junior Research Questions

At FSHA, we’ve just finished the massaging process and the results have been highly satisfactory. A few times I’ve squealed with delight at how far girls have come from point –a. Most students started out like Frances, and let me just show you where they’ve landed. Here are some research questions from the junior proposals:

[NOTE: many of these are informal drafts, so please excuse the lack of punctuation, etc.]

How does Walt Disney’s selection of “Sleeping Beauty” among other fairy tales indicate the timeless endurance of this type of story telling and what, if any, modifications to sleeping beauty did [Disney] make in order to modernize and sanitize the story for american families?

What can we tell about America’s national identity by studying the three major controversies that are apparent in American animation: Race and gender stereotyping, sexual connotations, and political and social views, and how they have been presented in these programs over time? More specifically, how has the unspoken divide between children’s animated programs and adult animated programs demonstrated the evolution of what we consider acceptable to share with our children?

Topic selection will make or break them at that point, so it feels good to know that we’re leading them through it at least three times (formally) between 10th and 12th grades.

Does hotel occupancy defy the loss of income among middle class Americans during the recession time (2007-2012)? Or, does the trend in hotel occupancy reflect a more permanent loss of middle class Americans? (Is the middle class shrinking?)

How does institutionalized racism play a role in the media’s portrayal of black individuals involved in crimes? What proactive measures can be used to make the media more open about properly discussing the race issues our society faces today?

How do social media innovations, like Tinder, continue to promote casual sexual encounters and devalue emotional attachment in today’s hookup culture? How have women’s tendencies pertaining to sexual freedom evolved in response to these innovations?

How does the American ad industry sexualize women with breast cancer, and how does this affect breast cancer research?

These are really good questions. Not all of them are perfect, but when you consider that these are 16-year old girls at the very, very, very beginning of their junior projects, it’s pretty impressive. They’ve managed to take a personal interest and make it an academic one. This is not always simple (in fact, it’s often not even allowed), yet it’s considered a tacit requirement for many entry-level college assignments. In a few years, they’ll be told to choose a topic, any topic, that relates to x, and then produce something, probably a paper, with a certain number or source requirements by a certain date. Topic selection will make or break them at that point, so it feels good to know that we’re leading them through it at least three times (formally) between 10th and 12th grades.

Next up, source literacy. Eeks, what’s that?